Kate* first began struggling with symptoms of bipolar disorder when she was 19 years old. A college freshman away from home for the first time, she struggled to make sense of what was happening, and turned to alcohol and drugs as a way of coping with symptoms she didn’t understand…symptoms of a mental illness that hadn’t yet been diagnosed. She stopped attending her classes and left college later that semester, ashamed but still unable to understand what had happened.

After returning home, Kate’s parents tried to help. Their first stop was the family’s longtime primary care doctor, who prescribed an antidepressant and suggested she see a therapist. She did, but her symptoms continued to get worse instead of better. Kate was unable to maintain employment or continue her education, and she felt hopeless.

“It was hard to see what there was to live for,” says Kate. “It was like I was living someone else’s life that I had no control over, and no future to look forward to.”

Over time, Kate received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and worked with a psychiatrist to find the right medication to help her manage her symptoms. She also started working with a new therapist who used a word Kate hadn’t heard before: recovery.

“No one had told me that I could ‘recover’ from my mental illness before that day,” said Kate. “It gave me hope for the future.”

Kate eventually finished college and now has a successful career. She has also become an advocate for mental health recovery and access to treatment and services people need to get better.

“It took me a long time to get better, and it’s my hope that my story helps others get help sooner. I also want health care professionals to know how important it is to provide hope for recovery to those facing mental illness…for me, that was life changing.”

The concept of “recovery” is still a fairly new one in the world of mental health treatment and services. Until the 1950s, many people facing mental illness lived in state institutions. Limited options for treatment existed, and there was little hope for those facing mental illness and their families that things could ever get better.

Today, we look at mental health very differently. The belief that recovery from mental illness is possible is prevalent. There are many more options for treatment and services for those living with mental illnesses. Although we still have a long way to go to ensure that people have access to the help they need to recover, we have come a long way.

Still, mental health recovery does not always mean “complete” recovery from a mental illness, at least not in the same way that recovery is often thought of when it comes to physical health concerns. For many people living with mental illness, recovery is about managing a chronic condition (and its symptoms) and building the resiliency, tools and support system they need to live a meaningful life.

The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines recovery as “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.”

At Mental Health Minnesota, we refer to a mental health “recovery journey,” because we know that ups and downs often occur, and no two paths to recovery are the same. We believe that engagement is where recovery begins, because it ensures that those living with mental illness know the options for care and treatment that are available and make choices that reflect their goals and individual journey to mental health recovery. The first step, however, is often having the resources and help needed to move forward.

Alex* called Mental Health Minnesota from a hospital after learning he would be discharged the next day. Prior to going to the emergency room and his ensuing hospitalization, Alex saw a primary care physician a few times per year but did not have a support system set up to address his mental health concerns, although he was taking several medications prescribed by his doctor to help address his symptoms.

Alex wanted to seek help, and felt that, following his mental health crisis and hospitalization, he needed an intensive treatment program to learn to manage his mental illness. However, he was also concerned that doing so would also mean loss of his full-time job, as well as his health insurance.

Mental Health Minnesota’s peer advocate helped Alex identify a partial hospitalization program and other resources, that would help him move toward mental health recovery, as well as make an appointment to see a psychiatrist. She also helped him contact human resources at his company to arrange for the leave he needed for treatment that would ensure that his employment and insurance were secure.

“I needed to keep my job, but I also knew that I needed help to get better,” said Alex. “Landing in the hospital meant I couldn’t continue to just ‘get by’…I needed more.”

For many people, the gateway to mental health care has become primary care, or in the event of a crisis, a hospital emergency room. So how can we all do more to make sure that people get the help they need, when they need it?

First, we should all recognize and appreciate the fact that mental health and physical health are, without a doubt, woven together. And for those facing serious mental illness, it’s not just a fact, it borders on a public health crisis.

People in Minnesota who are living with a serious mental illness die, on average, 24 years earlier than their peers. 24 years earlier. And while suicide is more common among those living with serious mental illness than the general population, the leading causes of death are heart disease, unintentional injury, COPD and cancer.

According to SAMHSA, this gap in life span has actually increased, not decreased, over the last thirty years. So, even as treatment and services for mental health have continue to improve, there is a need to further integrate the way we approach health care…physical health and mental health cannot be stand alone entities if we are to address this troubling trend.

Mental Health Minnesota initiated a survey recently to learn more about the barriers people living with a serious mental illness face in managing their health. We are hoping that our work will help health care providers think differently about their work and improve outcomes for their patients. A number of people completing the survey said that they felt their primary care doctor didn’t understand or address the individual barriers they were facing in pursuit of physical health, especially the impact of psychotropic medications, which can cause weight gain, lethargy and a number of other side effects.

So what can healthcare providers do? Ask your patients about their goals. Understand their challenges. Know when and where to refer a patient for more help. Look at the whole person. And know that one in five people will face a mental health concern at some point during their lifetime, and at one point or another, will walk through your office door.

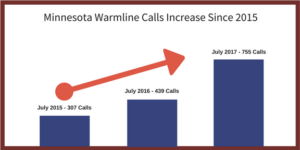

Founded in 1939, Mental Health Minnesota was the state’s first mental health advocacy and education organization. Services include the Minnesota Warmline, an anonymous phone line for those working on their mental health recovery, as well as Peer Advocacy, which helps people overcome hurdles and gain access to the treatment and services needed in their mental health recovery. Both services utilize a peer-to-peer approach, providing support to people through a lived experience perspective. Mental Health Minnesota’s free services are available to people across Minnesota, and health care providers are encouraged to refer patients who need help. For more information about services, resources and education, visit www.mentalhealthmn.org.

* Names have been changed to protect privacy.

This article was written by Shannah Mulvihill, Executive Director, and published in MetroDoctors Magazine in January 2017.